Written for Sunday morning worship at the Chapel of the Resurrection, Valparaiso University, Valparaiso, IN | 6th Sunday of Easter | May 22, 2022

Readings: Revelation 21:10, 22-22:5, John 14:23-29

The Book of Revelation was written for the people of Ukraine.

I don’t mean that literally, of course. I don’t mean that John of Patmos stood on an island 2,000 years ago and received a vision about a war that would happen in 2022. I don’t mean that if we carefully interpret all the weird symbols of Revelation – the horseman of the apocalypse, the beasts and dragons, the seals on the scroll – that they’ll point directly at specific events in our own time. I don’t think that those things, those words of God, have been lying dormant for thousands of years until they finally reached our ears in our time.

But still: the Book of Revelation was written for the people of Ukraine.

Because — all those strange Revelation symbols are there to make us think about realities that are true in every time.

That haunting number, 666, points to Caesar, and to all who use the power they have over people in ways that cause destruction and suffering.

The monsters represent things like enemy military power and lies and even just plain, evil death.

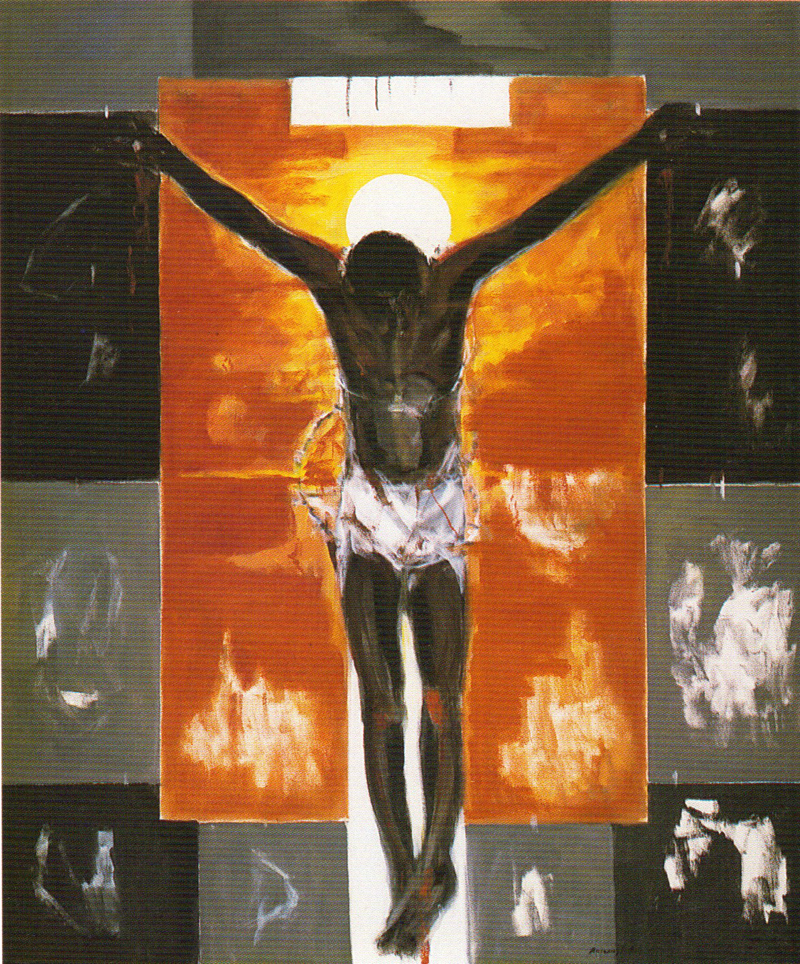

All those strange symbols are there to make us think about these things differently – from God’s perspective. From the perspective of Easter – of Christ’s resurrection – his triumph over all these powers.

Revelation points to the end goal of the resurrection: the day when “God will cage the monsters that plague humanity and deal with evil forever.”

The passage from Revelation that Kuda read for us a few moments ago comes after all our monsters have been conquered. Cruel rulers, lies, even “Death and Hades” (Rev. 20:13) have been conquered by Jesus. We are given a vision of the fulfillment of God’s plan, God’s promises.

Do you remember the story of the exodus from Egypt? God hears the cries of the people of Israel, the crying out from their lives of slavery, lives full of abuse and death. God hears; God sees; and God responds (Ex. 2:23-25). God enters their situation: through Moses, as a pillar of fire by day and a pillar of cloud by night, God is with God’s people, and God saves them.

Do you remember the story of the fiery furnace? The faithful Jews Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego refuse to obey the command of the King of Babylon and worship a false god, and so they are thrown into a furnace that is heated seven times beyond its usual fire. But when the king gazes into the flames, he sees not three figures, but four – “and the fourth has the appearance of a god.” The three men are saved (Daniel 3).

Do you remember the story of the Gospel of John, chapter 1? It’s that beautiful passage that begins, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” And then it tells us: “the Word became flesh and lived among us.” And as John unwraps this story, it emphasizes more than any other Gospel that in Jesus we see and hear and feel God, right here among us in all of our sickness and suffering and sin. God comes to save us.

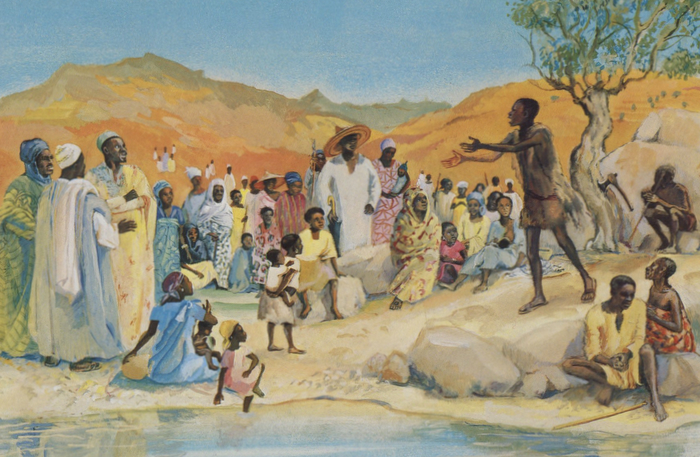

This is what our faith tells us God does over and over. The holy, eternal God enters into moments in our time, into the midst of our troubles, when we are surrounded by evil that seems so much greater than us. God comes to us, and God saves us.

The end of Revelation is the ultimate of these stories. Once again our holy God comes to earth, comes to us. John of Patmos saw a vision of the “holy city of Jerusalem coming down out of heaven from God.” He saw that there was no Temple in this city, no special holy building for people to go and seek God – because God was there, in the midst of the city.

This vision is full of promises: the promise that God is stronger than every power of this world. The promise that God always cares for those who suffer. And the promise that one day God will conquer all the death-dealing powers for good.

And if we listen to today’s passage like it’s music, we’ll hear one sound ringing through over and over again: Life. Life. Life. The Book of Life. The Water of Life. The Tree of Life.

God vanquishes all the death-dealing powers, and God fills every corner of creation with life.

Not survival. Not just staying alive. Not struggling to make ends meet; not living in fear; not fleeing home to escape violence.

God’s new creation flows with the kind of life that we long for. The Bible offers us images of God’s new creation that help us imagine…

A world so peaceful that a wolf and lamb can share a home (Isaiah 11:6-9).

A world without scarcity and without hunger, without the fear and greed that so often create scarcity – a world so abundant and generous that we will all have enough good food to eat (Isaiah 55:1-2).

A safe world, where God’s children don’t have to worry about being driven from their homes (Amos 9:13-15).

A united world, with healing for all nations, where we come together in the light of God’s truth and grace.

That is the resurrection promise that God offers through the book of Revelation. Ultimate, everlasting victory over the powers of evil that feel so overpowering to us. All its weird symbols are there to help us imagine our world from the vantage point of heaven – of victory – of true life. So that image, that imagination, could be with us in our world now, in our situations.

In Ukraine. In Buffalo. In hospitals. In prisons.

That ability to imagine life from the vantage point of heaven, victory, and true life is one of the great gifts of the Holy Spirit. A gift that we are given now. A gift that is powerful right now.

Through the Spirit, God makes us hope in the midst of destruction.

God makes us find light in the darkest night.

God makes us feel peace in chaos.

Jesus said, “..the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you everything, and remind you of all that I have said to you. Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled, and do not let them be afraid.”

Let us pray.

Creator of the universe, you made the world in beauty, and you restore all things in glory through the victory of Jesus Christ. We pray that, wherever your image is still disfigured by poverty, sickness, selfishness, war, and greed, the new creation in Jesus Christ may appear in justice, love, and peace, to the glory of your name.

You stand among us in the shadows of our time. As we move through every sorrow and trial of this life, uphold us with knowledge of the final morning when, in the glorious presence of your risen Son, we will share in his resurrection, redeemed and restored to fullness of life and forever freed to be your people. Amen.

Bibliography

The Bible Project, “Overview: Revelation 1:11,” YouTube, 14 December 2016. Accessed 20 June 2022.

“Overview: Revelation 12-22,” YouTube, 14 December 2016. Accessed 20 June 2022.

Christopher Rowland, “Revelation,” Global Bible Commentary, ed. Daniel Patte, (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2004), pp. 559-570.